Latest on COVID-19

- Home

- Latest on COVID-19

The Preparedness Problem — how America spent 20 years getting ready to fight a pandemic, and then dropped the ball when it finally arrived.

The nation’s health secretary was warned about a possible pandemic — and, he admits now, he didn’t take that first warning seriously enough. But he studied with experts at the Centers of Disease Control. He read papers on virology. He took his concerns to the president. And months later, the administration unveiled a plan to tackle the virus emerging out of Asia, investing in therapies and warning Americans to stock up on canned goods.

It’s a moment that feels ripped from the headlines about the current coronavirus crisis. But the year was 2005, not 2020.

And for his troubles, that health secretary — Bush appointee Mike Leavitt — was mocked as an alarmist by political rivals and late-night comics, even as that year’s threat of avian flu petered out around the globe.

“Secretary of Health and Human Services Michael Leavitt recommended that Americans store canned tuna and powdered milk under their beds for when bird flu hits,” host Jay Leno said on the Tonight Show in 2006, a recurring bit where he ridiculed Leavitt’s warnings. “What? … Powdered milk and tuna? How many would rather have the bird flu?”

Speaking to POLITICO this month, Leavitt described a trap that health and national security officials know too well: Prepare too early and you’re called Chicken Little. Act too late — and millions may die.

“In advance of a pandemic, anything you say sounds alarmist,” Leavitt explained. “After a pandemic starts, everything you’ve done is inadequate.”

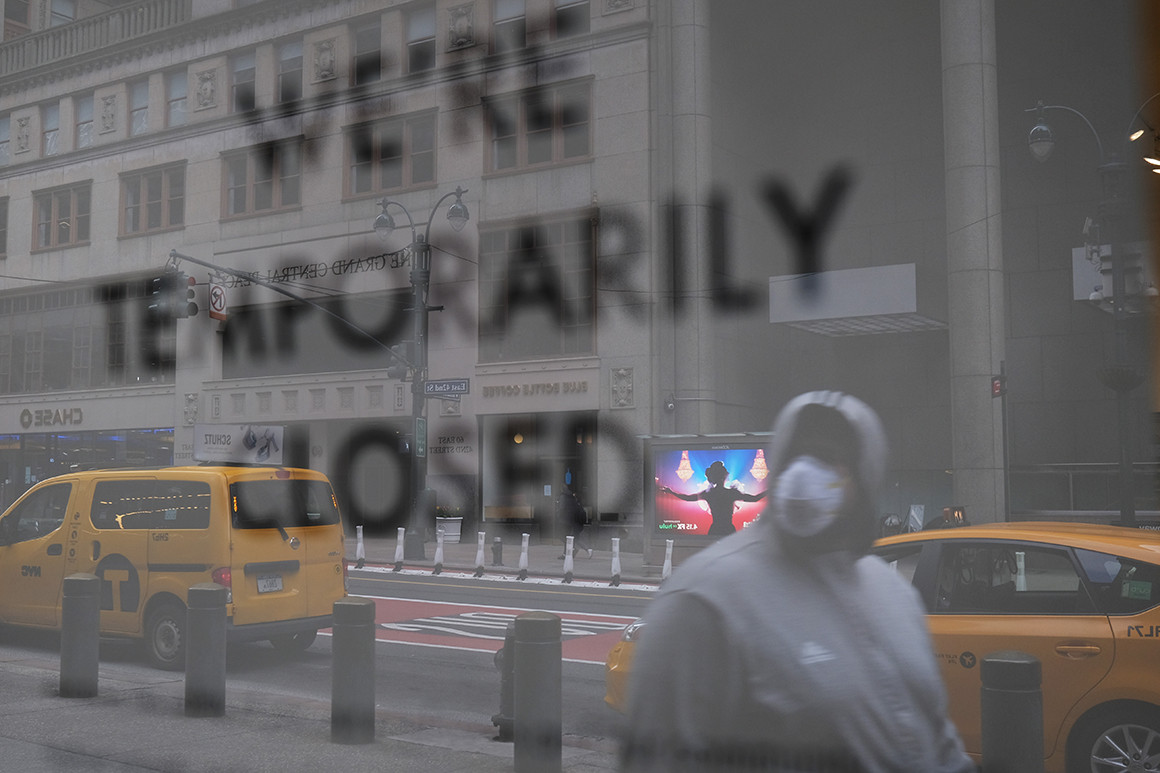

The Trump administration has taken the brunt of the blame for America’s lack of preparedness for the Covid-19 pandemic, which has caught the world’s wealthiest nation embarrassingly off-guard and plunged it into an economic and health catastrophe. But the cycle of inattention has roots far deeper than that, according to interviews with top policymakers from three administrations covering 20 years.

After each major health crisis of the last two decades, American health and political leaders have launched preparedness programs and issued blunt warnings to their successors — only to watch as those programs were defunded, staff was allowed to depart and Washington forgot the stark lessons it had just learned.

That cycle then accelerated during the tumultuous Trump administration, said the health officials interviewed for this story, nearly all of whom cited Trump’s willingness to disregard evidence and stick with his gut as the coronavirus threat menaced the nation.

In interviews and reviews of years of remarks, Leavitt and more than a dozen other current and former officials who led or shaped preparedness efforts across the Bush, Obama and Trump administrations described a two-decade evolution in how government leaders learned to fight killer viruses — and how America forgot those hard-won lessons as the Covid-19 outbreak loomed.

Government agencies slowly abandoned their pandemic-planning efforts, with the Homeland Security department in 2017 shelving its decade-plus efforts to devise models of how outbreaks affect the economy. Rather than train government staff to respond to a pandemic, as some high-level officials urged, FEMA in 2018 instead coordinated a massive mock exercise across nearly 100 federal departments focused on a hypothetical Washington, D.C., hurricane — even though federal officials had responded to three real-life hurricanes the year before and called the simulation unnecessary.

“We felt we were not prepared for a pandemic and needed to build muscle memory in the way that only a national exercise could do,” said Katrina Mulligan, who was the Justice Department’s top preparedness official at the time, reflecting the kind of would-have, could-have thinking among many ex-policymakers interviewed for this story. A former FEMA official told POLITICO that it was too late in the planning process to shift to a pandemic exercise.

Meanwhile, White House budget officials repeatedly rebuffed requests to fund the nation’s emergency stockpile, turning down the health department’s $1.5 billion-plus proposal in early 2019 and asking Congress for $705 million instead.

And even as the coronavirus threat arrived this January, the National Security Council set aside a step-by-step playbook carefully crafted by the Obama administration and career officials – based on their own sometimes rocky experiences dealing with H1N1 and Ebola -- for an ad hoc process that’s left the White House running consistently days or weeks behind on its response.

New reports are emerging near-daily about officials whose warnings fell on deaf ears.

Now, the Trump administration is facing the biggest public health threat in a century — relying on some of the same career officials and experts who advised Bush and Obama on pandemics to shape their coronavirus strategy today. Top infectious-disease scientist Anthony Fauci has been an Oval Office staple since the Reagan administration, although his delicate clashes with Trump over drugs and policy have tested the 79-year-old’s political survival. Meanwhile, Trump’s health secretary Alex Azar and top health preparedness official, Robert Kadlec, have gone from understudies during Bush-era health crises to main characters in this response.